System Maintenance

The Pane Maintenance

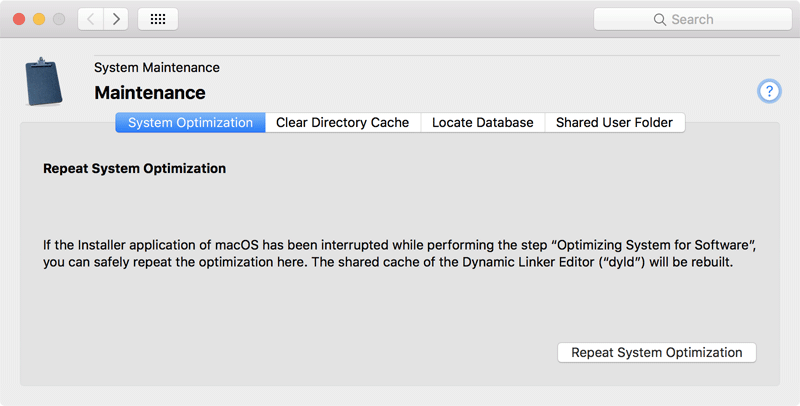

System Optimization

All applications you launch are dependent on services of the operating system: The programs are using features of the system, for example to receive click messages from the mouse, or to open windows on screen. Technically speaking, this means that each application has to link its own program code with the code libraries of the operating system. Programs typically use several thousand functions available in the system which have to be “located” while the application is starting. These locations, namely the file paths where the code libraries are stored, and the exact byte positions within the libraries are not necessarily fixed: They may change from OS version to OS version, so the applications have to do a lot of work checking and locating all these OS functions at launch time.

Applications try to accelerate this link process at start time by assuming that the code locations remain constant as long as no new operating system updates have been installed since the last launch. They store the required code locations of operating system functions in a cache area in their own program code. So the next time the application is launched, it can simply reuse this saved information and does not need to repeat the whole search process of locating the OS functions. The cache only needs to be rebuilt if the application detects that new system libraries have been installed.

This optimization technique is called prebinding. It speeds up the launch time of programs, but does not accelerate the programs themselves. This technique is not restricted to applications only. It is even more important for the system libraries themselves, because they are also using each other’s functions. For example, the library drawing windows on screen uses features of the graphics library, and the graphics library uses functions of the system kernel. For this reason, code libraries and similar software components, like plug-ins, make use of prebinding, too, although they don’t really have a “startup phase.”

As mentioned in the previous paragraphs, each application “re-prebinds” itself to the available libraries when it detects that new libraries have been installed, for example as part of an OS update. In order to anticipate this step, it is a good idea for an upgrade installer to simply tell all applications on the computer to re-prebind themselves during, or more precisely, just after the update has been installed. The macOS Installer indeed performs this step as last part of each system update. It is done when the message “Optimizing system for installed software” is shown.

It is one of the macOS myths that the system no longer uses any kind of prebinding. This is not true, although many Internet pages claim it does. The truth is that modern system versions indeed use a new improved linking technique which eliminates the need of prebinding for applications and third-party code libraries. System libraries are still prebound, however, and they benefit from this optimization.

This means that if a system update installation was somehow interrupted, or if you manipulated one of the system libraries (for example by “downgrading” a specific library via a Time Machine backup) all prebinding information in the system should be updated. To manually initiate a system-wide prebinding process, perform the following steps:

- Open the tab item System Optimization of the pane Maintenance.

- Click the button Repeat System Optimization.

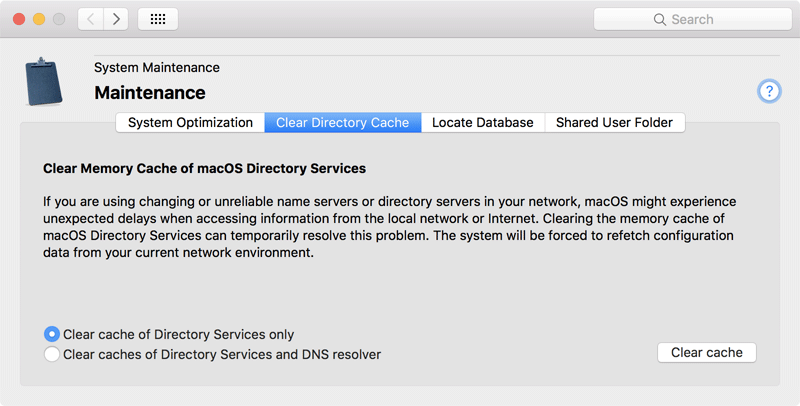

Clear Directory Cache

macOS contains a background service which communicates with the directory services configured for your system. This service is the central information broker needed to collect data about users, computers, IP addresses, user groups and many other things relevant to an operating system. Under special circumstances, the internal memory contents of this service may contain incorrect or outdated information, especially if your computer is accessing a name server or directory server which doesn’t work reliably, or if the network configuration has changed abruptly. This can result in unexpected delays (spinning rainbow cursor) especially when using network functions.

In this situation, clearing the online cache of directory services might correct the problem. The information broker will begin with fresh new data which it fetches from your network and the local computer. Note that this cache is not stored in any file. It is kept in the memory (RAM) of the directory services subsystem of macOS.

The word “directory” is sometimes used as a technical term for a folder storing files. This is not what is meant here. In this context, the word directory refers to an inventory list of names, objects and network addresses relevant to your computer. macOS is always running a directory service no matter whether the computer is connected to a network or not.

When retrieving data about names and network addresses of other computers, the directory services are not the only source of information which keep records in their internal cache memory for some time. The system service acting as “DNS resolver,” responsible for finding addresses for computer names and vice versa, assists the directory services in doing their job. When you clear the memory cache, you can decide whether only the records of directory services as such should be cleared, or if cached DNS information should be removed as well.

To clear the directory cache of macOS, perform the following steps:

- Open the tab item Clear Directory Cache of the pane Maintenance.

- Select one the radio buttons to indicate if the cache of the DNS resolver should be included in the cleaning operation.

- Click the button Clear Cache.

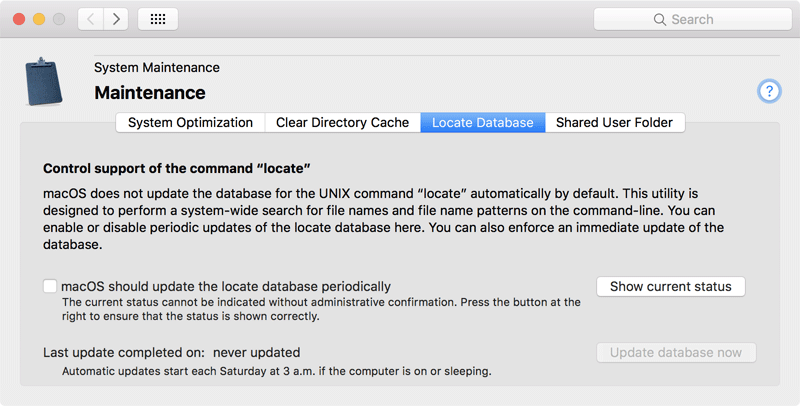

Locate Database

Because macOS is a UNIX system, it comes with the program locate, a command-line application which quickly finds files by their names or parts of their names. locate usually finds names more quickly than Spotlight and includes both visible and invisible files in its search. Like Spotlight, locate needs an internal database to do its job. This database is updated in regular intervals to ensure that the program has current information about new and deleted files.

Because most users don’t work with macOS command-line programs, the automatic service that updates the locate database is switched off by default. Only administrative users are allowed to check whether the service is on or off. Perform the following steps to see if the update service is active or not:

- Open the tab item Locate Database of the pane Maintenance.

- Click the button Show current status.

The current state will now be displayed by the check mark at macOS should update the locate database periodically. You can now either set the check mark to activate automatic maintenance of the database, or remove the check mark to shut down this service.

In a default installation of macOS, the system will update the locate database automatically each Saturday at 3:15 a.m. If your computer is off or in sleep mode at that time, the update is automatically postponed to a later date where the system is active. To enforce an immediate update of the locate database “now,” click the button Update database now.

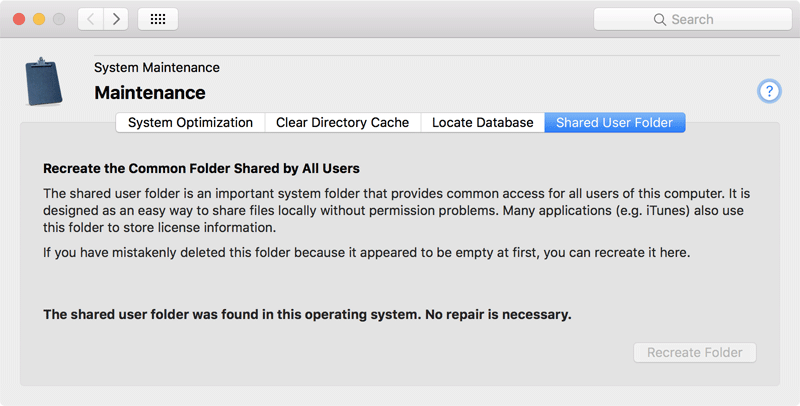

Shared User Folder

macOS provides a special folder on the system volume which can be found at Users > Shared. The folder is designed to be utilized by all accounts of a Mac, sharing files locally for common usage. Sharing of data is made possible by specific settings that grant read and write permissions to everyone. At the same time, other settings ensure that only the creator (and hereby owner) of a file has the right to delete this file at a later time, without the risk to inadvertently remove data of others users.

Many applications by Apple and other vendors use this folder as well, to automatically save data that could be interesting to all users. This includes license or registration data. For example, iTunes uses hidden contents in this folder to store licensing information for the use of copyright-protected media.

Some users remove this important system folder because it is initially empty and appears to serve no obvious purpose. This can lead to failures and errors in many applications, however. Due to the special settings for this folder, it is not easy to recreate it correctly.

TinkerTool System checks whether the folder exists on your Mac. If not, you can choose to recreate it in its correct original form, hereby repairing the operating system.

- Open the tab item Shared User Folder of the pane Maintenance.

- Click the button Recreate folder.